SUBMISSION FROM PROFESSOR JACK W PONTON, FRENG

Your remit refers to: …the merits of the targets, and what the risks and barriers are to realising them.

However the specific questions, around which you ask for submissions to be based appear to address only the last of these. I wish to comment on the merits of the targets and the risks of attempting to achieve them. I shall thus not be able to respond to the questions as requested.

Merits of the Targets

In setting targets for renewables there is the implicit assumption that their achievement will be of benefit greater than any damage caused by their pursuit. The claimed benefit most frequently cited, and perhaps uppermost in public perception of renewable energy, is that of climate change amelioration.

Whether on not climate change is in fact occurring and being driven by man made carbon dioxide emissions (my own scientific training leads me to believe that it probably is) one should consider whether a UK or Scottish renewables programme will have any significant effect on these emissions.

Readily available statistics, and simple arithmetic, show clearly that it will not.

A typical medium sized (25 MW installed capacity) wind farm at a realistic 27% load factor would, using the BWEA’s factor of 430g CO2/kWh, remit about 25,000 tonne of CO2 per annum. Such figures are regularly given by developers with the implication that this is a significant amount. In fact it would represent a trivial 0.005% of the UK’s annual emissions of around 500 million tonnes (Mte). China (in 2010) is estimated [1] to have emitted 8950 Mte of carbon dioxide. Thus a typical UK wind farm will remit in a year about 1.5 minutes of China’s current emissions.

Of the UK total, around a third is probably attributable to electricity generation. Between 2008 and 2009 China’s emissions increased by more than 900Mte and India’s by 130Mte [2]. If the entire UK fossil fuel generation capacity were to be replaced by renewables tomorrow, in about two months Asia would have added emissions to completely negate any reduction. By some estimates [3] China alone will build 500GW of coal fired power stations in the next four years. The UK has added no coal fired capacity since 1986.

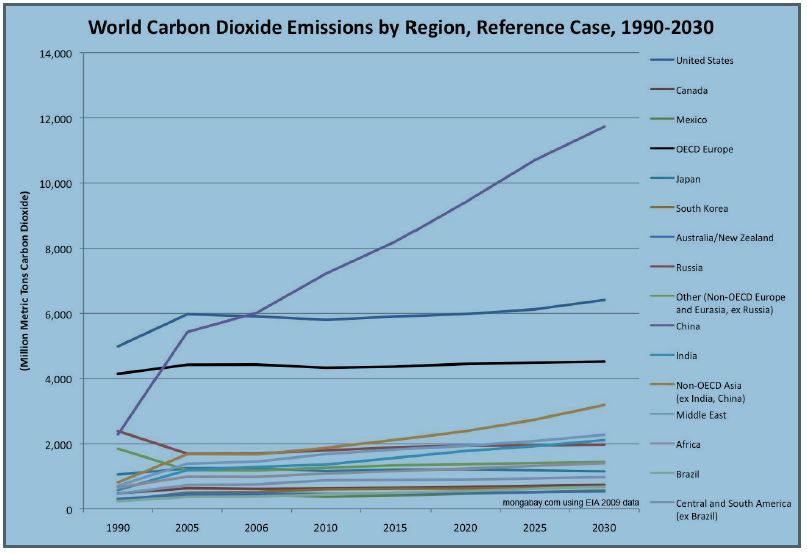

The situation is strikingly illustrated by the graph above. Note that this is based on IEA 2009 figures which appear to be significant underestimates in the light of later figures. It predicts China’s 2010 emissions to be 7000Mte compared with the current estimate [1] of 8950Mte.

It is argued that developing countries such as China have lower per capita emissions and are thus `entitled’ to increase their total. In fact China’s 6.8te per head in 2010 exceeds that of both Spain and Portugal. The UK’s figure of 8.1te per person in 2010 will be at worst stable. As China’s population is now essentially stabilised, if its emissions increase by 10% annually, less than either its historic or current rate, it will overtake the UK on a per capita basis within three years.

The suggestion is also made that if the West demonstrates a commitment to emission reduction, then China will feel morally obliged to follow suit. This is not just naïve, it is laughable.

If man made carbon dioxide is causing climate change, then climate change will happen regardless of actions taken by the UK, let alone by Scotland.

Scotland’s 2009 total annual greenhouse gas emissions were 51MTe [5]. 42% of this is 21.4Mte, or 20.9 hours of current emissions from China. The Scottish Government’s targets represent annually less than one day’s emissions from China .

Risks

The risks of pursuing the current renewables targets are to both the economy and energy security.

Most of Scotland’s electricity currently comes from two nuclear, one coal fired and one gas fired power station.

Together with long existing hydro and recently installed wind these are a more than adequate provision and Scotland is currently a net exporter of electricity to England.

However, much of this conventional capacity in due to close within the time frame necessary for the construction of new large scale plant.

At the present moment, there are no plans for any significant new or replacement generation capacity other than wind farms. This is not surprising, as the consumer paid subsidies for wind make this the only rational investment decision for energy companies.

It has been repeatedly pointed out that availability of renewable generating capacity is at the mercy of the elements rather than under the control of the operator. This is particularly true of wind generation, where at any given time actual energy produced can be between zero and 100% of nominal capacity, with an average of about 27%.

The target of ‘100% of Scotland’s electricity’ from renewables is an ambiguous statement, but taken with the absence of investment in any other generation capacity it has two unambiguous consequences.

Installed renewables capacity would have to significantly exceed current conventional capacity by nearly a factor of four due to the 27% average capacity of wind generation. When it is very windy, much more electricity would be produced than can be consumed in Scotland.

The assumption made in setting renewables targets is that this electricity can be sold profitably to England.

However, unlike with conventional generation, operators will not be able to choose when this occurs. It may well be at 3am on a summer night when demand is minimal, and when England’s own wind farms are at full production.

The experience of Denmark, with around 20% of renewable generation, is that surplus electricity has to be sold at a minimum price. Denmark has the most expensive electricity in Europe, if not the world. Turbines can of course be turned off, but this represents a waste of expensively developed resources, and under the present regime of `constraint’ payments to producers actually costs consumers more than giving the electricity away.

No matter how many wind turbines are built there would be times when demand exceeds effective renewable generation capacity as there is little or no wind. This is most likely to happen when there is Europe-wide high barometric pressure on the coldest winter days.

Between November 2008 and December 2010 there were 124 occasions when UK wind farms were producing less than 1.25% of their average capacity (and thus about 0.3% of their theoretical capacity). At each of the four highest peak demands in 2010, UK wind output was between 2.5% and 5.5% of capacity [4].

Scotland’s winter energy security would thus have to depend on imports from England. This presupposes that a) England has the necessary capacity to provide it, b) that they are prepared to sell it and c) that we can afford to buy at what will be a premium price when England’s, and probably most of Europe’s, own wind generation is also inoperative.

There is an energy security risk that Scotland will lack access to conventional generation capacity resulting in power shortages in the coldest periods of the winter. .

There is the economic risk that Scotland would be selling electricity at its lowest prices and buying at its highest. No estimate of the cost to the economy and consumers has been made by government.

References

[1] Long term trend in global CO2 emissions, PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, for the European Commission, 2011.

[2] International Energy Agency figures cited by The Guardian, January 2011.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2011/jan/31/world-carbon-dioxide-emissions-country-data-co2

[3] Nomura, cited by The Economist, p62, Jan 29 2011.

[4] Analysis of UK Wind Power Generation November 2008 to December 2010,

Report by Stuart Young Consulting for the John Muir Trust, March 2011.

[5] Scottish Government,

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2011/09/06123057

Professor Jack W Ponton, FRENG

29 February 2012

European Platform Against Windfarms

European Platform Against Windfarms